The Sea as Frontier

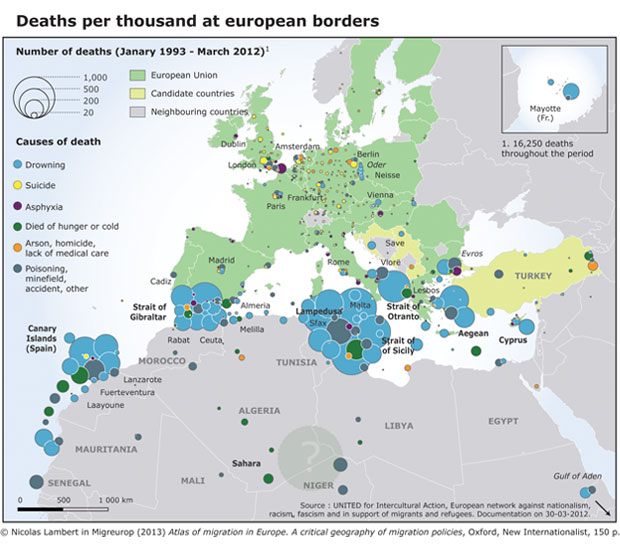

More than 13.000 deaths by policy

The death of migrants and the violation of their rights in the Mediterranean Sea is a long-standing phenomenon. Between 1988 and May 2012, more than 13.000 deaths have been documented at the maritime borders of the EU, and more than 6.000 in the Sicily Channel only.[1] These deaths are first and foremost the result of the EU’s policy of closure. With the progressive introduction of a common European visa policy and the concurrent denial of legal access to non-European migrants, the latter have been forced to resort to dangerous means of entry, amongst others embarking on unseaworthy vessels. There are several combined factors that have contributed to turning the Mediterranean into a deadly liquid border.

The militarisation of the Mediterranean

Through a series of policies and practices, the Mediterranean has been increasingly militarised and progressively transformed into a frontier area that extends far beyond the legal perimeter of the EU. National border guard agencies of European coastal states first deployed maritime border patrols using boats, helicopters and airplanes to intercept incoming migrants. Put under pressure by their EU counterparts, the EU’s neighbouring countries increasingly adopted similar practices to prevent the departure of their nationals and non-nationals. In addition, as of 2006, Frontex, the European border management agency, has coordinated the deployment of additional means and personnel sent by member states. Finally, in the frame of its “Operation Active Endeavour” launched after 9/11 with the aim of providing a deterrent presence against the “threat” of terrorism in strategic waters of the Mediterranean, NATO has repeatedly participated in the detection of illegalised migrants as part of the “civilian” dimension of its mission. This increasing militarisation of the maritime borders of the EU has not succeeded in the stated aim of stopping the inflow of illegalised migrants, rather it has resulted in the splintering of migration routes towards longer and more perilous points of passage.[2]

An electromagnetic frontier

Remote sensing is central to “securitisation” of the EU’s maritime borders. This practice is led by border control agencies as well as other actors who attempt to monitor maritime traffic to insure the flow of “wanted” mobility. For the crossings and deaths of migrants at sea occur within one of the most densely travelled maritime areas in the world [3], a congested sea as one can sea by observing automated vessel tracking data mandatory for large commercial ships (AIS) provided by Marinnetraffic.com. Maritime surveillance then consists in “sorting” amongst the several hundreds of thousands vessels that cross the sea annually and detect “threats”. To this effect, optical and thermal cameras, sea-, air- and land-borne radars, vessel tracking technologies and satellites constitute a vast and complex remote sensing apparatus. These surveillance means are central to EU border agencies, which, through the practice of “pre-frontier detection” increasingly attempt to detect migrants before they enter EU waters so that the EU’s neighbouring countries are responsible to intercept or “rescue” them.[4] However, while all these technologies of surveillance are geared at blocking “unwanted” movements of people, they can also be used against the grain to document violations at sea, which is what WatchTheMed seeks to do.

Conflicting maritime jurisdictions

Finally, the maritime frontier also has a legal dimension, with overlapping and conflicting divisions that extend throughout the high seas, far beyond the territorial waters that mark the limit of states’ full sovereignty (for more details see “Rights at Sea”). Maritime jurisdictions represent a form of “unbundled” sovereignty, in which the state’s rights and obligations that compose modern state sovereignty on the land are decoupled from each other and applied selectively. This allows states to extend their capacity to control vessels beyond their boundaries, but also attempt to retract themselves from the obligations defined by national and international law.[5] Since the enforcement of the so-called Dublin Regulation which sets out that the first state of entry of an asylum seeker in the EU is responsible for following his or her claim, coastal states have been increasingly hesitant to disembark migrants intercepted at sea and have practiced “push-backs” - deporting them without considering their claim to asylum. Rescue at sea too as become increasingly politicised. While the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR), adopted in Hamburg, has led to the division of the seas into Search and Rescue (SAR) zones within which states are responsible to coordinate rescue, some states such as Tunisia and Libya have not defined their SAR zones, while others such as Italy and Malta have overlapping SAR zones and are signatories to different versions of the SAR convention. This leads to constant diplomatic rows as to which state is responsible to operate rescues. In addition, coastal states also frequently refuse to disembark migrants who have been rescued by seafarers. In some instances, assistance has even been criminalised, with those lending assistance to migrants in distress being criminally charged with facilitating illegal immigration. Combined, these practices have led to repeated cases of non-assistance to people in distress at sea.

A never-ending journey at the borders of the EU

The sea has thus become a vast frontier zone, in which a policy of closure, militarisation, electromagnetic surveillance and conflicting jurisdictions combine to produce deaths and legal violations. Those who succeed in crossing the sea encounter further manifestations of the EU’s border regime on the land: detention, legal and material precarity, exploitation, deportation. The sea is thus just one stage in a larger border regime that aims to govern the mobility of migrants “before, at and after the border”, expanding outside and within the EU’s territory itself.

While the EU’s maritime frontier extends far beyond the reach of the public’s gaze, WatchTheMed aims to enable actors defending the rights of migrants at sea to exercise a “right to look” at sea and hold states accountable for the deaths of migrants and the violation of their rights.

While the EU’s maritime frontier extends far beyond the reach of the public’s gaze, WatchTheMed aims to enable actors defending the rights of migrants at sea to exercise a “right to look” at sea and hold states accountable for the deaths of migrants and the violation of their rights.

Footnotes

[1] For more information see: http://fortresseurope.blogspot.com and http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/pdfs/listofdeaths.pdf

[2] For more information see Migreurop’s yearly reports available at www.migreurop.org as well as its Atlas of Migration in Europe : A critical geography of migration policies, Oxford, New Internationalist, 2013.

[3] Ameer Abdulla, PhD, Olof Linden, PhD (editors). 2008. Maritime traffic effects on biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea: Review of impacts, priority areas and mitigation measures. Malaga, Spain: IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation. 184 pp. p. 7

[4] See Ben Hayes and Mathias Vermeulen, Borderline - The EU's New Border Surveillance Initiatives, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, July 2012. URL: http://www.boell.de/downloads/DRV_120523_BORDERLINE_-_Border_Surveillance.pdf

[5] See Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen &Tanja E.Aalberts, Sovereignty at Sea: The law and politics of saving lives in the Mare Liberum, DIIS Working Paper 2010:18, and Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero, Jurisdictional Waters in The Mediterranean and Black Seas, European Parliament, 2010.